Updated August 29, 2020

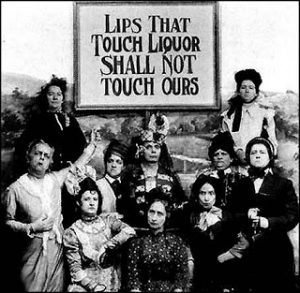

One hundred years ago, two major constitutional amendments went into effect. The 18th marked the start of Prohibition and the 19th granted many women the right to vote. It wasn’t a coincidence that these laws went into effect adjacent to one another. The movements were linked in some surprising ways.

Advocates for temperance linked the consumption of alcohol with greater issues like violent crime, poverty, unemployment, and domestic violence.

Advocates for temperance linked the consumption of alcohol with greater issues like violent crime, poverty, unemployment, and domestic violence.

As the United States developed, its people started turning from light alcoholic beverages, such as beer and hard cider, to stronger beverages like rum and whiskey as they became cheaper.

The production of rum especially was part of the whole slave trade. Slaves from Africa were brought to the West Indies to grow sugar, which was used to make rum. That’s why it started to become available so cheaply. What many citizens saw as an epidemic of alcoholism followed.

Remember that at this time, women had no rights. A woman was legally not a person, and was considered to be the property of her father or husband. So what happened if a woman got married to a man who turned out to be an alcoholic? If he spent all their money on booze, or even became violent? Legally, there was no escape. What could women do? All they could do was ask men to stop drinking so much. That’s how the rise of cheap alcohol and growing alcoholism led to the growth of the women’s temperance movement in the early 19th century.

In midwestern states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin, where brewers and liquor interests occupied a preeminent economic position, “wets” feared the temperance inclinations of women.

In this new documentary, “A Brief History of Women in Bars: A Minnesota Story in Three Rounds,” Fulbright Fellow, historian, and podcaster Katie Thornton looks at how the state’s temperance movement set the stage for its women’s suffrage movement. But she also looks at how temperance leaders—and, by proxy, many early suffragists—failed to engage many women who weren’t wealthy, White, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. And the Minnesota women who didn’t fit that bill empowered themselves in other ways—sometimes through the economic and social opportunities presented by the alcohol industry.